Perfect competition – a pure market

Perfect

competition describes a

market structure whose assumptions

are strong and therefore unlikely to exist in most real-world markets.

Economists have become more interested in pure competition partly because of the

growth of

e-commerce as a means of buying and selling goods and

services. And also because of the popularity of

auctions as a

device for allocating scarce resources among competing ends.

Assumptions for a perfectly competitive market

- Many sellers each of whom produce a low percentage of

market output and cannot influence the prevailing market price.

- Many individual buyers, none has any control over the

market price

- Perfect freedom of entry and exit from the industry. Firms

face no sunk costs and entry and exit from the market is

feasible in the long run. This assumption means that all firms in a perfectly

competitive market make normal profits in the long run.

- Homogeneous products are supplied to the

markets that are perfect substitutes. This leads to each firms

being “price takers” with a perfectly elastic demand curve for

their product.

- Perfect knowledge – consumers have all readily available

information about prices and products from competing suppliers and can access

this at zero cost – in other words, there are few transactions costs involved in

searching for the required information about prices. Likewise sellers have

perfect knowledge about their competitors.

- Perfectly mobile factors of production – land, labour and

capital can be switched in response to changing market conditions, prices and

incentives.

- No externalities arising from production and/or

consumption.

Evaluation – Understanding the real world of imperfect

competition!

It is often said that perfect competition is a market structure that belongs

to out-dated textbooks and is not worthy of study! Clearly the assumptions of

pure competition do not hold in the vast majority of real-world markets, for

example, some suppliers may exert control over the amount of goods and services

supplied and exploit their

monopoly

power.

On the demand-side, some consumers may have

monopsony

power against their suppliers because they purchase a high percentage

of total demand. Think for example about the

buying power

wielded by the major supermarkets when it comes to sourcing food and drink from

food processing businesses and farmers. The

Competition

Commission has recently been involved in lengthy and detailed investigations

into the market power of the major supermarkets.

In addition, there are nearly always some

barriers to the contestability

of a market and far from being homogeneous; most markets are full of

heterogeneous products due to

product

differentiation – in other words, products are made different to

attract separate groups of consumers.

Consumers have

imperfect information and their preferences

and choices can be influenced by the effects of

persuasive

marketing and

advertising. In every industry we can

find examples of

asymmetric information where the seller knows

more about quality of good than buyer – a frequently quoted example is the

market for second-hand cars! The real world is one in which

negative and

positive externalities from both production and consumption are

numerous – both of which can lead to a divergence between private and social

costs and benefits. Finally there may be imperfect competition in related

markets such as the market for key raw materials, labour and capital goods.

Adding all of these points together, it seems that we can come close to a

world of perfect competition but in practice

there are nearly always barriers

to pure competition. That said there are examples of markets which are

highly competitive and which display many, if not all, of the requirements

needed for perfect competition. In the example below we look at the global

market for currencies.

Currency markets - taking us closer to perfect

competition

- The global foreign exchange market is where all buying and selling of world

currencies takes place. There is 24-hour trading, 5 days a week.

- Trading volume in the Forex market is around $3 trillion per day –

equivalent to the annual GDP of France! 31% of global trading takes place in

London alone.

- Most trading in currencies is ‘speculative.’

The main players in the currency markets are as follows:

- Banks both as “market makers” dealing in currencies and

also as end-users demanding currency for their own operations.

- Hedge funds and other institutions (e.g. funds invested by

asset managers, pension funds).

- Central Banks (including occasional currency intervention

in the market when they buy and sell to manipulate an exchange rate in a

particular direction).

- Corporations (for example airlines and energy companies who

may use the currency market for defensive ‘hedging’ of exposures to risk such as

volatile oil and gas prices.)

- Private investors and people remitting money earned

overseas to their country of origin / market speculators

trading in currencies for their own gain / tourists going on holiday and people

traveling around the world on business.

Why does a currency market come close to perfect

competition?

- Homogenous output: The "goods" traded in the foreign

exchange markets are homogenous - a US dollar is a dollar and a euro is a euro

whether someone is trading it in London, New York or Tokyo.

- Many buyers and sellers meet openly to determine prices:

There are large numbers of buyers and sellers - each of the major banks has a

foreign exchange trading floor which helps to "make the

market". Indeed there are so many sellers operating around the world that the

currency exchanges are open for business twenty-four hours a day. No one agent

in the currency market can, on their own influence price on a persistent basis -

all are ‘price takers’. According to Forex_Broker.net "The intensity and

quantity of buyers and sellers ready for deals doesn't allow separate big

participants to move the market in joint effort in their own interests on a

long-term basis."

- Currency values are determined solely by market demand and supply

factors.

- High quality real-time information and low transactions

costs: Most buyers or sellers are well informed with access to

real-time market information and background research analysis on the factors

driving the prices of each individual currency. Technological progress has made

more information immediately available at a fraction of the cost of just a few

years ago. This is not to say that information is cheap - an annual subscription

to a Bloomberg or a Reuter’s news terminal will cost several thousand dollars.

But the market is rich with information and transactions costs for each batch of

currency bought and sold has come down.

- Seeking the best price: The buyers and sellers in foreign

exchange only deal with those who offer the best prices. Technology allows them

to find the best price quickly.

What are the limitations of currency trading as an example of a

competitive market?

- Firstly the market can be influenced by official

intervention via buying and selling of currencies by governments or

central banks operating on their behalf. There is a huge debate about the actual

impact of intervention by policy-makers in the currency markets.

- Secondly there are high fixed costs involved in a bank or other financial

institution when establishing a new trading platform for currencies. They need

the capital equipment to trade effectively; the skilled labour to employ as

currency traders and researchers. Some of these costs may be counted as sunk

costs – hard to recover if a decision is made to leave the market.

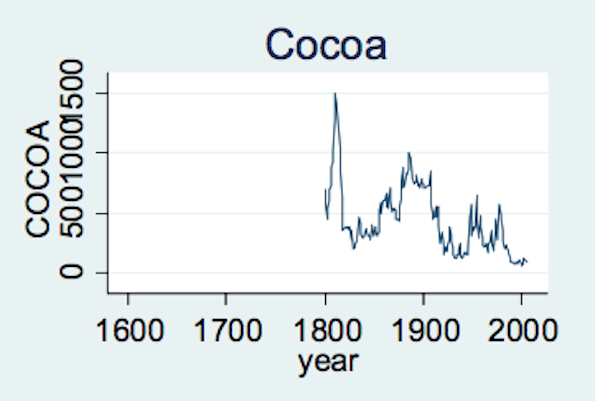

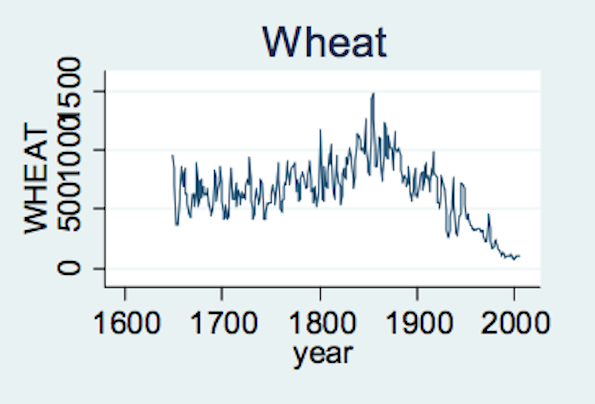

Despite these limitations, the foreign currency markets take us reasonably

close to a world of perfect competition. Much the same can be said for trading

in the equities and bond markets and also the ever expanding range of future

markets for financial investments and internationally traded commodities. Other

examples of competitive markets can be found on a local scale – for example a

local farmers’ market where there might be a number of farmers offering their

produce for sale.

The internet and perfect competition

- Advances in web technology have made markets more competitive. It has

reduced barriers

to entry for firms wanting to compete with well-established businesses – for

example specialist toy retailers are better able to battle for market share with

the dominant retailers such as ToysRUs and Wal-Mart.

- One of the most important aspects of the internet is the ability of

consumers to find information about prices for many goods and services. There

are an enormous number of price

comparison sites in the UK covering everything from digital cameras to

package holidays, car insurance to CDs and jewellery.

- That said the price comparison web sites themselves have come under

criticism. For example the sites offering to compare hundreds of different motor

insurance policies or mortgage products draw information from the insurance and

mortgage brokers but might use limiting assumptions about the different types of

consumers looking for the best price – the result is a range of prices facing

the consumer that don’t accurately reflect their precise needs – and consumers

may only realise this when, for example, they make a claim on an insurance

policy bought over the internet which turns out not to provide the specific

cover they needed.

- And in the market for price comparison sites there is monopoly power too!

Moneysupermarket.com currently has around 40% of the overall comparison site

market, with Confused.com its nearest rival with a share of about 10%.

Price and output in the short run under perfect

competition

- In the short run, the interaction between demand and supply determines the

“market-clearing” price. A price P1 is established and output

Q1 is produced. This price is taken by each firm. The average revenue curve is

their individual demand curve.

- Since the market price is constant for each unit sold, the AR curve also

becomes the marginal revenue curve (MR) for a firm in perfect competition.

- For the firm, the profit maximising output is at Q2 where

MC=MR. This output generates a total revenue (P1 x Q2). Since total revenue

exceeds total cost, the firm in our example is making abnormal (economic)

profits.

- This is not necessarily the case for all firms in the industry since it

depends on the position of their short run cost curves. Some firms may be

experiencing sub-normal profits if average costs exceed the price – and total

costs will be greater than total revenue.

The adjustment to the long-run equilibrium in perfect

competition

The adjustment to the long-run equilibrium in perfect

competition

- If most firms are making abnormal profits in the short run,

this encourages the entry of new firms into the industry

- This will cause an outward shift in market supply forcing down the price

- The increase in supply will eventually reduce the price until price

= long run average cost. At this point, each firm in the industry is

making normal profit.

- Other things remaining the same, there is no further incentive for movement

of firms in and out of the industry and a long-run equilibrium has been

established. This is shown in the next diagram.

We are assuming in the diagram above that there has been no shift in market

demand.

- The effect of increased supply is to force down the price and cause an

expansion along the market demand curve.

- But for each supplier, the price they “take” is now lower and it is this

that drives down the level of profit made towards normal profit equilibrium.

In an exam question you may be asked to trace and analyse what might happen

if

- There was a change in market demand (e.g. arising from

changes in the relative prices of substitute products or complements.)

- There was a cost-reducing innovation affecting all firms in

the market or an external shock that increases the variable costs of all

producers.

Adam Smith on Competition “The natural price or the

price of free competition ... is the lowest which can be taken. [It] is the

lowest which the sellers can commonly afford to take, and at the same time

continue their business.”

Source: Adam Smith, the Wealth of Nations

(1776), Book I, Chapter VII

Characteristics of competitive markets

The common characteristics of markets that are considered to be “competitive”

are:

- Lower prices because of many competing firms. The

cross-price elasticity of demand for one product will be high

suggesting that consumers are prepared to switch their demand to the most

competitively priced products in the marketplace.

- Low barriers

to entry – the entry of new firms provides competition and ensures

prices are kept low in the long run.

- Lower total profits and profit margins than in markets

which dominated by a few firms.

- Greater entrepreneurial activity – the Austrian school of economics

argues that competition is a process. For competition to be

improved and sustained there needs to be a genuine desire on behalf of

entrepreneurs to innovate and to invent to drive markets forward and create what

Joseph

Schumpeter called the “gales of creative destruction”.

- Economic efficiency

– competition will ensure that firms move towards productive efficiency. The

threat of competition should lead to a faster rate of technological diffusion,

as firms have to be responsive to the changing needs of consumers. This is known

as dynamic efficiency.

The importance of non-price competition

In competitive markets,

non-price competition can be crucial

in winning sales and protecting or enhancing

market

share.

Perfect competition and efficiency

Perfect competition can be used as a

yardstick to compare

with other market structures because it displays high levels of

economic

efficiency.

- Allocative

efficiency: In both the short and long run we find

that price is equal to marginal cost (P=MC) and thus allocative efficiency is

achieved. At the ruling price, consumer and producer surplus are maximised. No

one can be made better off without making some other agent at least as worse off

– i.e. we achieve a Pareto optimum allocation of

resources.

- Productive efficiency: Productive efficiency occurs when

the equilibrium output is supplied at minimum average cost. This is attained in

the long run for a competitive market. Firms with high unit costs may not be

able to justify remaining in the industry as the market price is driven down by

the forces of competition.

- Dynamic efficiency: We assume that a perfectly competitive

market produces homogeneous products – in other words, there is little scope for

innovation

designed purely to make products differentiated from each other and allow a

supplier to develop and then exploit a competitive advantage in the market to

establish some monopoly

power.

Some economists claim that perfect competition is not a good market structure

for high levels of

research and development spending and the

resulting

product and process innovations. Indeed it may be the

case that monopolistic or oligopolistic markets are more effective long term in

creating the environment for research and innovation to flourish. A

cost-reducing innovation from one producer will, under the assumption of perfect

information, be immediately and without cost transferred to all of the other

suppliers.

That said a

contestable

market provides the discipline on firms to keep their costs under

control, to seek to minimise wastage of scarce resources and to refrain from

exploiting the consumer by setting high prices and enjoying high profit margins.

In this sense, competition can stimulate improvements in both

static and

dynamic efficiency over time.

The long run of perfect competition,

therefore, exhibits optimal levels of economic

efficiency.

But for this to be achieved

all of the conditions of perfect competition

must hold – including in related markets. When the assumptions are

dropped, we move into a world of

imperfect competition with all

of the potential that exists for various forms of market failure