I don't think anybody has any idea what the economic impact of Brexit will be. Steve Eisman

Total Pageviews

Sunday, 31 January 2016

Wednesday, 27 January 2016

Unit 3: Tesco abusing its market power?

Tesco "knowingly delayed paying money to suppliers in order to improve its own financial position", the supermarket ombudsman has found.

Click here for article.

Useful when discussing the market power of monopsonies and the effectiveness of regulators.

Click here for article.

Useful when discussing the market power of monopsonies and the effectiveness of regulators.

Monday, 25 January 2016

Unit 4: Exchange rates in the news

Some excellent (and topical) articles on recent exchange rate crisis. Each clip gives a valuable insight into why exchange rates fluctuate and how the rate movements can impact on an economy.

Thanks to Geogg from tutor2u for the storify piece

Thanks to Geogg from tutor2u for the storify piece

Unit 4: Causes of a current account deficit - essay hints

Economist Ed Huang looks at this question on the balance of

payments:

"Evaluate the

causes of persistent current account deficits for developed or developing

countries”.

A

current account deficit happens when there is a net outflow of currency from a

country on the trade, investment income and transfer account. It is an almost

inevitable consequence of trade that there will be imbalances in doing so, thus

some countries are left in surplus, others in deficit – and many stay in one of

these two camps for extended periods of time. It is not difficult to observe

that the UK has been subject to one such persistent current account deficit.

Having not experienced current account trade surplus for 30 years now, the

evidence is clear – despite the best claims the current Conservative party are

making about the future. Of course, the UK is far from the only country with a

current account deficit, but there are clearly different causes for different

nations that lead to an imbalance in trade.

One potential cause of a persistent current account deficit

is that of sustained economic growth. Growth in an economy is indicated by a

sustained rise in its real GDP, which in turn must mean that the total income

of the nation has increased. If the incomes of at least some of the individuals

within the economy are rising, then almost certainly a proportion of this

increase will be spent on imported goods and services. In developing economies,

this may be especially true as economic growth may coincide with changes in

tastes towards luxury and higher-tech goods, which are often imported from

developed nations.

Thus economic growth has a direct link to an increase in the

value of imports which, ceteris paribus, will lead to an increase in the

current account deficit. This is evident in economies such as Ethiopia and

Rwanda, who both have current account deficits in excess of 10% of GDP, but are

two of the fastest growing nations globally (10.3% and 7.7% respectively).

However, this much depends on the marginal propensity to

import of the nation. This concept can be defined as the proportion of an

additional unit of income that will be spent on imported goods. If the marginal

propensity to import is high, then a rise in income (characterised by economic

growth) will have a larger effect on the current account deficit than if it is

low, since it implies that the level of imports will vary closely with changes

in income.

The UK population has a characteristically high MPM, so the

current account deficit is far more sensitive to growth rates than other

countries – particularly those with high import tariffs (Djibouti has an

average 18% tariff compared to the US’ 1.5%). Furthermore, the marginal

propensity to import also varies between individuals in a nation. Some classes

(especially those reliant on commodity imports, such as the steel processing or

energy generation industries) are more likely to spend a greater proportion of

additional income on imported goods than others. Thus if the economic growth is

concentrated in sectors with high MPMs, then the changes in the current account

deficit will be magnified compared to if the rise in output and income is

located in sectors with low MPMs.

Furthermore, it could be argued that high current account

deficits caused by high growth rates are unsustainable, and therefore perhaps

not persistent (depending on one’s interpretation of the word). In the case of

Rwanda and Ethiopia, such a large deficit will drain foreign reserves and –

given that at least part of the deficit is caused by an inflow of borrowed

money used to close the savings gap between investment and savings – accumulate

debt. Extended periods of high current account deficits are therefore

unsustainable in the long term, although if the deficit is used to build

critical infrastructure that can later serve a self-sustaining economy, then

there need not be one indefinitely.

Extended periods of high inflation can also lead to

persistent deficits in the current account. High inflation indicates that the

prices of domestic goods and services are rising rapidly, and this can mean

that domestic production becomes less competitive compared to imported goods

and services, since it is becoming comparatively more expensive relative to

abroad. One such example would be Turkey, where inflation was 9% in 2013 and

the current account deficit was a sizeable 5% of GDP.

However, this can be entirely offset if inflation is

similarly high – or even higher – in the countries where the imported goods

originate from. If prices are rising not just domestically, but also abroad,

then there is no change in competitiveness and thus no effect on the balance of

payments. In the case of Turkey, were inflation to be equally high within the

EU (where over 50% of its imported goods originate from), then this would offset

its high inflation as there would be no significant change in price

competitiveness between foreign and domestic goods, ceteris paribus.

Finally, economies can also be subject to persistent current

account deficits if their levels of investment are too low to allow for exports

of high (or even moderate) value items. For instance, economies with low levels

of investment may have to rely on exports of raw, unprocessed commodities that

have the potential to be greatly increased in value if they were processed on

site. Examples would include oil exports in Angola (where 80% is exported as

unrefined crude oil), and coffee plantations in Ethiopia (where many of the

beans are left unprocessed on site, to be roasted once they are exported). This

results in price-uncompetitive exports, lowering the country’s export

capabilities and thus worsening the balance of payments. This may also include

too little investment in human capital (i.e. insufficient spending on

education), which translates into low productivity (so high unit labour costs

and therefore uncompetitive goods and services), as well as a lack of the

skills necessary for higher skill jobs.

Countries

such as Romania (where there has been a sharp growth in the IT sector in the

last couple of decades) can benefit from higher-value goods and services being

exported per worker compared to other economies where human capital levels are

lower, and thus where the value of goods produced per worker is also less.

Insufficient levels of investment will therefore lead to the inability to

export high-value goods and services, and thus may mean a diminished total

value of exports and thus a worse current account deficit.

Unit 4: Exchange rates - Barmy Army on tour

The Barmy Army on tour in South Africa, where the Rand is depreciating fast. What are the implications for the South African economy? (both positive & negative)

Sunday, 24 January 2016

A2 Economics: Revision Guide

Published in 2009, but still really useful to get a refresher on theoretical concepts.

Thursday, 21 January 2016

Unit 3: Price discrimination - updated presentation

This is an updated revision presentation of the economics of price discrimination

as a pricing strategy for businesses in imperfectly competitive markets.

as a pricing strategy for businesses in imperfectly competitive markets.

Students should be able to:

- Explain and evaluate the potential costs and benefits of monopoly to both firms and consumers, including the conditions necessary for price discrimination to take place

- Diagrams should also be used to support the understanding of price discrimination

Wednesday, 20 January 2016

Unit 2: Inflation explained

This is a short introductory piece on inflation from the Guardian.

Inflation is one of the most important concepts in economics. It’s also one of the simplest. It’s just the average rate that prices are rising.

A small amount of inflation is healthy for an economy - but how is it calculated and what happens when it gets out of control?

Tuesday, 19 January 2016

Unit 2 & 4: Essential Reading - UK Economy 2015

This is essential for all students studying macro economics. It has up to date data on the performance of the UK economy. Extremely useful when applying theory to real world situations.

Monday, 18 January 2016

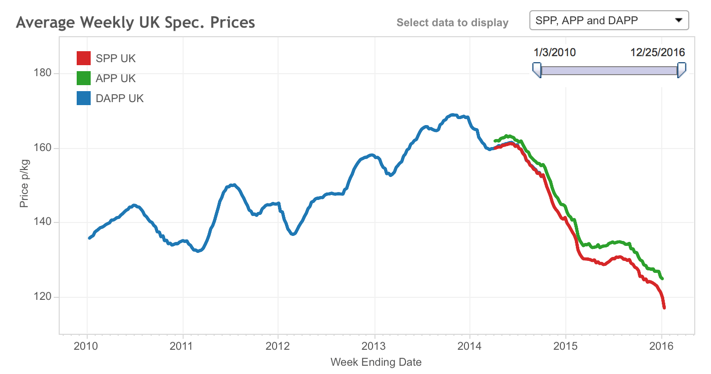

Unit 1: Pig Prices

The Chinese economic slowdown, Russia’s ban on European food imports and cheaper pork products from other EU producers are combining to create a perfect storm for many of the UK's pig farmers.

It has become hard to make both ends meat, indeed on some estimates, pig farmers in the UK are making a loss of £7 or more on each pig reared. Many are leaving the industry and now more than half of the pork products bought in the UK come from imported meat. The industry is trying to find new markets for export, but there is inevitably a delay in achieving this.

The economic problems facing pig producers are similar to the crisis facing the UK milk sector. To what extent is there a case for state aid in some shape or form to help pig producers through the current crisis?

The economic problems facing pig producers are similar to the crisis facing the UK milk sector. To what extent is there a case for state aid in some shape or form to help pig producers through the current crisis?

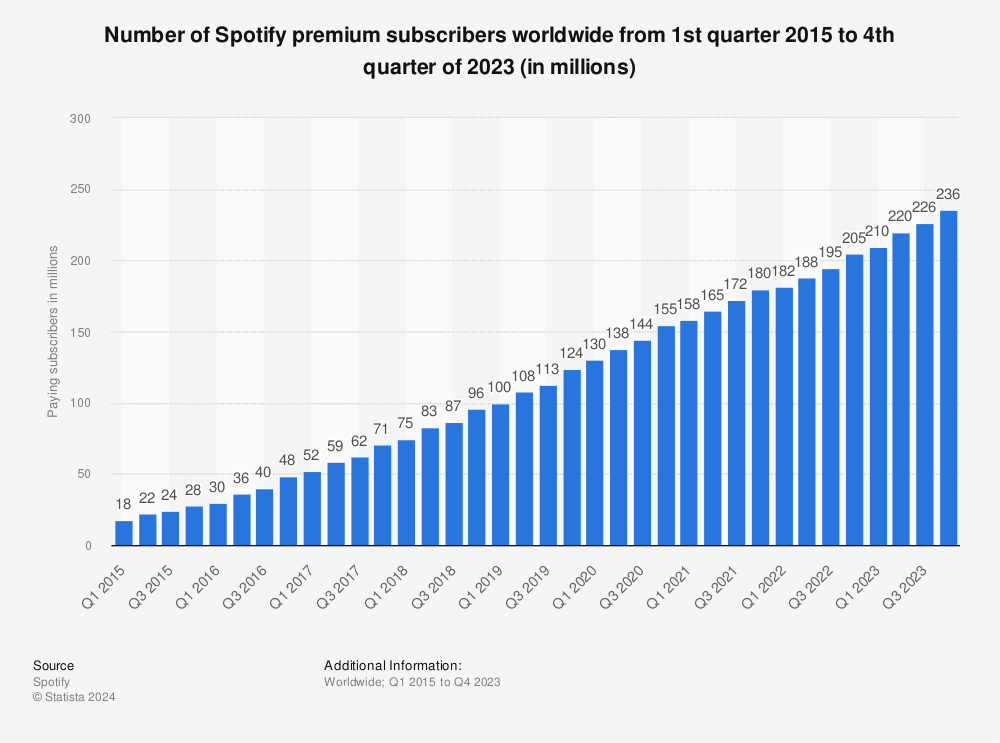

Unit 1: Cross Price Elasticity of Demand - Music streaming & Album Sales

The growing popularity of relatively low-priced music streaming from services such as Apple Music and Spotify is coming at the expense of other market segments. This is a good example of cross price elasticity of demand in action.

Apple music now has in excess of 10 million subscribers and Spotify’s subscriber baseis estimated to be 25-30 million with a much larger advert-supported free tier of active users.

A report on the US music industry from Neilson found that Justin Bieber’s album set an all-time record for total audio on-demand streams when it was streamed more than 100 million times the week of its release.

CD album sales and album downloads last year declined by 11 and 3 percent, respectively, and digital track sales dropped by 12 per cent.

The vinyl countdown?

The only other format that is rising in popularity is vinyl. The format of analog music lovers continued its comeback in 2015 with a 29 percent increase in LP sales. This is good news for many smaller independent music stores who are the main driver of the recovery in vinyl sales.

The only other format that is rising in popularity is vinyl. The format of analog music lovers continued its comeback in 2015 with a 29 percent increase in LP sales. This is good news for many smaller independent music stores who are the main driver of the recovery in vinyl sales.

In the UK for example, Vinyl albums share of music albums sales in the United Kingdom (UK) has risen from 0.2% in 2009 to 1.5% in 2014.

Sunday, 17 January 2016

Unit 3: Supermarkets and successful price competition!

The final quarter and Christmas sales reports for many of the supermarkets are now beginning to emerge. The results are generally mixed, with Morrisons showing a slight increase in profits, Tesco faring better than expected but Sainsbury's seeing a slight drop.

What is an interesting aspect of a semi-revival in the 'Big 4' supermarket's fortunes (if you include Asda) is that price has become a key factor in the fight back against the discounters like Aldi and Lidl. 'Price Watch Promises' have helped the major supermarkets reduce fears of over-pricing by offering money back if products are sold cheaper elsewhere. Morrisons' success has been directly linked to price reductions.

This offers A Level economics students some nice analytical evidence. Traditional oligopoly theory suggests that supermarkets would not compete directly on price due to the kinked demand curve and game theory. This evidence counters that.

Click here for a report on Sainsbury's,

Here for a report on Tesco

and here for a report on Morrisons.

What is an interesting aspect of a semi-revival in the 'Big 4' supermarket's fortunes (if you include Asda) is that price has become a key factor in the fight back against the discounters like Aldi and Lidl. 'Price Watch Promises' have helped the major supermarkets reduce fears of over-pricing by offering money back if products are sold cheaper elsewhere. Morrisons' success has been directly linked to price reductions.

This offers A Level economics students some nice analytical evidence. Traditional oligopoly theory suggests that supermarkets would not compete directly on price due to the kinked demand curve and game theory. This evidence counters that.

Click here for a report on Sainsbury's,

Here for a report on Tesco

and here for a report on Morrisons.

Thursday, 14 January 2016

Wednesday, 13 January 2016

Saturday, 9 January 2016

Unit 4: Income inequality - analysis & evaluation

A billion people have been lifted out of poverty since 1990, but inequality has been rising in many other countries at the same time. So, how much inequality is too much? Many may recoil from such a question - inequality is a dirty word. But this programme isn't about fairness. This programme is about economics – and how far inequality affects growth and prosperity. Presented by the economist and broadcaster Linda Yueh.

Unit 3: Banking and the regulator - are they effective?

Click here to access an article published in Jan 2016 about the financial regulator (Financial Conduct Authority FCA).

In it, the interim chief executive of the Financial Conduct Authority has defended her record in regulating the banking sector. Useful for application & evaluation on the quality and effectiveness of the government regulators.

In it, the interim chief executive of the Financial Conduct Authority has defended her record in regulating the banking sector. Useful for application & evaluation on the quality and effectiveness of the government regulators.

Labels:

banking,

government regulation,

regulatory capture

Unit 3: Supermarkets and petrol pricing

In recent weeks we have heard numerous stories of supermarkets engaged in price

wars on the forecourt. The price of a litre of petrol has - in some localities -

fallen below £1 and further price cuts are expected with global oil prices dropping

to an eleven year low. One aspect of the market for petrol and diesel in the UK

is that supermarket prices are consistently below that of the UK average.

The data below tracks the monthly average price.

Why is the price per litre of petrol and diesel consistently cheaper in supermarkets compared to the UK average - here are some thoughts:

- Supermarkets have buying power (monopsony power) in the wholesale fuel market and can negotiate lower prices. Some supermarkets do not have long term purchase contracts and look to buy petrol and diesel in wholesale markets at the lowest price they can

- They are happy to accept lower profit margins on each litre sold as a strategy to get people into their stores - in some cases this might come close to loss leading (pricing below unit cost) and at the very least it involves a satisficing approach

- They can run petrol stations at lower cost because they already own the sites and they can strip out other costs by stocking their shops with their own brands

- The average price per litre includes the prices of many smaller independent petrol retailers whose prices are always higher because of a lack of economies of scale. That said the number of independent retailers has been in steep decline over the last 20 years

- Is supermarket petrol inferior to branded / premium fuels? All fuels sold in the UK conform to relevant standards but a debate rages on online motoring forums about the relative efficiency of supermarket fuels.

Labels:

petrol,

pricing strategies,

satisficing,

supermarkets

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)